Note: for clarity, I am going to ignore the questions such as where the coal, wood, and paper came from; how Karl obtained wire steel stock; etc.

“Today’s the day,” said Karl.

Gunnar looked up, surprised. He was busy rearranging his collection of animal bones, this time from the largest to the smallest. Sometimes he picked the prettiest one, sometimes the most bad-ass one (a broken skull of a fox), then arranged them in the badassery order. Strangely, the older he got, the less he enjoyed the game. Perhaps he just needed more bones. “The day?”

“The day you start working at the forge.”

Gunnar jumped up to his feet, dropping the large bone he was holding. It hit the skull, breaking it further, but the boy didn’t care. “I…will work at the forge? All on my own?”

Kids’ toys – Árbæjarsafn open air museum, Reykjavík

His father laughed. “No, Gunnar, you can’t work at the forge all on your own. You need a helper. Or, in this case, I need a helper. That will be you.”

The boy was overjoyed. He watched his father at work since the forge was built a year before. Karl was self-taught, or more precisely still self-teaching, explaining to Gunnar over and over again over the noise of the hammer and the roar of the fire that the most important thing about forging was practice, practice, practice. To Gunnar’s dismay, Karl had never made a sword. Yet. “Will I make swords?”

Karl emitted a sound somewhere between a sneeze and a chuckle. “Come, boy.”

Gunnar’s head was already filled with the images of himself making a huuuuuuge sword. One that would slay enemies in half before even touching them. So what that in the twentieth century nobody really needed swords? Gunnar wanted one. He could already see himself expertly handling the weapon. He ignored his mother raising her eyes from the shirt she was mending, then shaking her head. What did mother know about swords? Nothing, that’s what.

The humble beginning

“Here’s the broom,” said Karl. “Sweep the floor.”

“Oh…”

“Make sure it’s clean before we start.”

What’s the point, wondered Gunnar, trying to do his job both properly and as fast as possible. Clouds of dust – he would later learn that was half-coal dust, half-something called oxide – filled the air, and he began to cough.

“Too fast,” said Karl, observing him through the open door.

The boy forced himself to slow down and even managed – for a few seconds – before his hands started to shake with impatience. A sword. Really big one. “I’m done,” he announced. Karl shook his head, chuckling, but Gunnar was ready. Very big one. He didn’t think about the weight of such a sword, he just wanted to be a hero from the Sagas, no matter that nobody really ran around with swords anymore or chopped his enemies – that Gunnar didn’t have, but he would obtain a few if needed – into pieces.

“Let’s start the fire,” said Karl. “You’ll operate the blower.”

Photo: Magdalena Cristi Przyłucka, blacksmithing museum, Wojciechów, Poland. Note there are two types of blowers. They’re too close to the walls, but, well, it’s a museum, not an actual forge…

Gunnar, excited beyond belief, pulled at the blower as hard as he could and caused the construction his father was building from crumbled paper and little pieces of wood to fly into the air. “You’ll operate it when I tell you,” said Karl, still chuckling quietly, and Gunnar blushed. “Gently. Otherwise… you see what happens otherwise.”

When the paper was lit, Karl put some small pieces of wood on top, then added thicker ones. Only once the pile was burning bright did he start to add coal, bit by bit, until the fire looked like the one Gunnar always saw while his father was working.

“And now?” asked the boy greedily, leaving the blower alone.

“And now you will continue with the blower.”

“With the… but just for now, aye?”

“For the next few weeks, until you learn how to pump air at the right speed.”

“But…”

Karl’s smile disappeared and Gunnar returned to his previous position, sighing. The blower’s handles were heavy and it was surprisingly difficult to keep the air flow like his father wanted it. The anvil kept ringing with every blow of his father’s hammer as Karl worked on a horseshoe after horseshoe. Gunnar watched Karl’s hands moving, the metal turning yellow, the tongs tightening around the chunk before his father pulled it out, then flattened it before continuing. Horseshoes, thought Gunnar with certain disdain. Aye, horses needed to be shod, but what about the swords? With a sinking feeling in his stomach, the boy suddenly realised he had never seen his father make a sword, or even a lousy dagger…

Moving on

It took three weeks until his father allowed him to do anything but pump the air. There had to be some sort of more efficient way to do this, thought Gunnar. This was medieval, but in a bad way, one that had nothing to do with swords or axes. Big axes. Big, very sharp…

“Today,” announced Karl, “you will make your first nail.”

“My first…” started Gunnar, then his tone rapidly changed. “…Nail?”

Yes, Gunnar, nails. Those are the first items I’ve made, February 2012.

“You’ll be surprised at how difficult that is. Making a nail involves three techniques. One of them is called tapering, one is upsetting, and of course we have to make the nail head.”

Gunnar’s shoulders dropped. Three techniques? That sounded excruciatingly boring.

“But first,” said Karl, “you will brush the forge. It always has to be clean. If a client comes by, they have to see a clean place, not some sort of dirty mess.” He absent-mindedly swept the anvil with his hand and a small cloud of oxide – by now Gunnar knew it was called that, although he had no idea where it came from – flew into the air. “Clean. Those tongs – always arrange them by size. Hammers – always in place. That way you always know where everything is.”

Tapering, thought Gunnar. Upsetting. What was upsetting was the idea of making nails. He had never seen his father make anything as boring as nails, even though inexplicably a pile of them was always present in a large box. Perhaps a sword would come second, he hoped. Or he could sneak over here at night, maybe the noise would wake his parents up…

“Let’s start,” said Karl. “Make a fire yourself. I’ll operate the blower today. You have no idea how lucky you are.”

“…Aye?”

“Most people don’t get to make a nail after a few weeks. You should really spend half a year cleaning and working the blower…”

Gunnar’s face became so long he resembled a horse. Karl laughed heartily. “Start on the fire.”

Fire

Gunnar crumpled some paper hastily, then lit it with a match. Impatiently, he threw wood on top. The fire went out. “You’re not blowing,” he accused his father.

“No,” said Karl. “You’re trying to do it too fast. The paper has to be burning first. Then the wood, starting with thin, small pieces before those are burning, and then you can put thicker ones on top.”

Pro-tip: don’t use a non-dustproof phone in the forge for too long. February 2012, Wojciechów, Poland.

Oh, thought the boy. Indeed. That was how father did it, indeed. His hands shaky in excitement, he crumpled some more paper – he didn’t know or care where it came from – and waited, trying not to grind his teeth, until the flame was large enough. Small pieces of wood. Then larger ones. “Why is this so complicated? Can’t we just light the coal?”

“Try,” laughed Karl. “The paper produces hot flame, aye, but not hot enough. The wood makes it hotter. And only once the wood is burning, it’s hot enough to start lighting the coal. Patience, son, patience.”

Gunnar threw a few handfuls of coal in, trying to mimic his father’s technique. The fire went out and he instinctively reached into the pit to take out the coal and start again, then screamed.

“Put your hand in the water tank,” sighed Karl.

“It’s cold!”

“That’s the point. Unless you like burns on your hands.”

Gunnar kept his hand in the water for a few seconds. “I’m ready,” he announced. His father laughed again, then let Gunnar try again. This time, the boy used a small scoop to remove the hot fuel – not hot enough to produce the fire, but definitely hot enough to give him burns. Despite Gunnar’s impatience, his hand was hurting, but he wouldn’t let some pain stop him. If he had to make a nail before the sword, he would. Surely it couldn’t have been difficult?

Nail

Karl cut off a chunk of the stock. He first took a long piece, then heated it up before placing it on the cutting thing, which turned out to be called a hardy. The tool was inserted into a square hole in the anvil, then Karl placed the hot part of the metal on top and hammered it, at first quite hard, then gentler and gentler – to avoid hitting the hardy, he explained. Once it was cut, Gunnar immediately bent to reach for the hot chunk, which was already black again, so definitely not that hot…

Karl waited out the boy’s screaming, then instructed him to place his hand in the water tank again. Gunnar tried to contain the tears. He hadn’t started yet and his hand was already burnt twice.

“It’s safer to touch really hot steel,” observed Karl, “rather than the black heat. When the steel is hot enough to be cherry red at least, the burn immediately gets cauterised and closes. When you pick up something like this, you end up with blisters.”

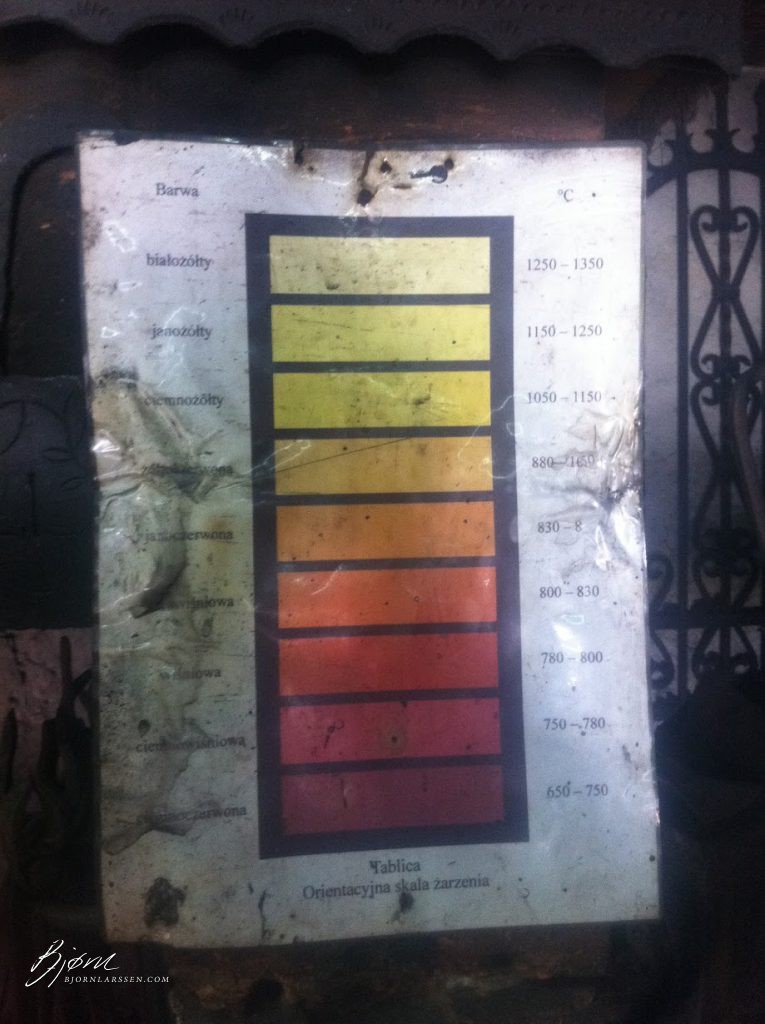

Steel colours and temperatures (Celsius). Note that cherry red starts at 650 degrees. Below 600 degrees you have what’s called “black heat” – the metal doesn’t look hot, but you definitely don’t want it in your hand. A simple way to check the temperature is to place your hand above the metal and check whether it seems hot.

Cauterised, thought Gunnar, confused by the new word. Cherry red. It certainly didn’t look like a cherry to him. This time he kept his sore hand in the water tank a bit longer, while Karl gently pulled at the blower to keep the flame steady, but not too tall. “Use tongs next time,” he suggested and Gunnar picked a pair. “Ones that are the right size. Those are too large. You need tongs with an opening that’s the same thickness as the stock. Yes, those. How’s your hand?”

It hurts like hell. “Perfect. Never better.” His father laughed again and Gunnar’s cheeks, red from the cold, turned even redder – and warmer. “It’s cold in here,” he said.

“Of course it is. It’s winter and the windows are open.”

“Can’t we close them?”

“This smoke and dust are bad for your lungs. The forge needs to be aired.”

Water tank next to the fire. Er. Ice tank. Temperature outside: -24 Celsius (11 Fahrenheit). Temperature inside: -24 Celsius (11 Fahrenheit). Fire temperature: it’s not that big, so let’s say 1300 degrees. Next to the fire: my first attempts at upsetting.

“But there is a, eh, chimney…”

Karl just pointed around. “Why do you think you have to clean up every morning? I don’t come here at night to throw the dirt around.”

“There isn’t any yet,” muttered Gunnar before remembering that, indeed, there was no dust around because they hadn’t done anything yet.

“If your hand is fine, then you can start.”

Upsetting

“At first,” said Karl, “you will flatten both ends. You heat up just one end, then use a smaller hammer to flatten it.” The cut was uneven, angular. “You place the flatter end on the anvil, then hit the other one with the hammer until it’s flat.”

Gunnar smashed the metal with the hammer and it immediately bent.

Obviously not a nail, but this is what happens when you are upsetting. I made my job much harder by creating the sharp end first.

“Smaller hammer,” said Karl. “Not so hard.”

But… blacksmithing was all about hitting things really hard, thought Gunnar. He never paid much attention to how exactly his father used the hammer and the tongs. “I can’t hold it like this!”

“Those tongs have a little indentation here. See? This is how you hold it vertically.” Karl took over the tools, letting go of the blower and letting the flame nearly die out before he returned the metal into the fire. “The goal is to make it look like a mushroom. That will be the head of the nail. You have to do this before you sharpen the other end.”

The aforementioned indentation for holding the round stock vertically.

“Er, why?”

“Because once you sharpen the other end, you can’t upset this one. The stock has to rest on the anvil, flat. When you have a sharp end, you’re going to ruin it completely – and you won’t get any upsetting done. Remember – the hotter it is, the better, but don’t let it get white hot, or you’ll burn the metal and you’ll have to start again. I’ll make sure there’s not too much air coming. The more air, the more coal, the hotter the fire gets.”

Gunnar spent good twenty minutes on the upsetting, straightening with gentle blows, ending up bending the metal. His father showed him how to flatten it again, then produced a tool Gunnar had never seen before. “This is called a monkey tool.”

Nail head

“What is it for?”

“It will help you avoid further bending when you’re making the nail head.” Karl placed the upset chunk of steel inside the tool. “See? The straight part goes inside, the one you upset doesn’t. Now you can flatten it… not yet! When it’s hot, silly boy. Get it to yellow heat.”

“It’s already almost black,” complained Gunnar once he smashed the upset part three times.

“That’s because the nail is heating the tool itself. The tool is cold, your nail is hot. Think about when you heat the soup. The bottom gets hot and you can burn it before the soup itself is even warm. When you stir it, you distribute the heat.”

“But I’m not stirring anything!” Gunnar’s hand was sore, there was indeed a blister, except it wasn’t there anymore, because the handle of the hammer already opened it and rubbed the skin off, exposing the delicate flesh.

My hand after the first day of work. You don’t need so much strength to make smaller items, actually. You need calluses.

“It’s a metaphor,” sighed Karl. “I don’t know how to explain it better. In any case, heat it up again. You’ll learn how to do it in one go. Once you’ve made a hundred…”

Gunnar’s face became slightly green. He was suddenly grateful for the faint light inside the forge.

“…you will be able to make a nail within less than a minute. In two heats. A heat is when you heat it up…”

“I know! I mean, I guessed. Sorry.”

“Aye. No problem. Do it again.”

This time Gunnar flattened the entire nail head. “What now?”

“It’s not symmetrical,” observed Karl. “You don’t just smash it randomly. You have to make sure it’s centered.”

Gunnar swallowed. He expected this to be fun.

“Let’s start again,” said his father. “You’ll get it soon. You don’t just hit it straight from the top when you notice it’s starting to bend. You have to make sure it’s straight. Don’t smash it so hard. Once you know what you’re doing, you’ll need to hit it a few times, for now try to do it slowly…”

“When do I sharpen the other end?”

“First you have to learn how to make the nail heads. By the way, if you don’t sharpen the other end, it becomes a rivet. You use rivets to connect two pieces of metal, and then they need two heads.”

“How…?”

“Next time,” said his father good-humouredly. “Once you’ve learned upsetting and making the head. Let me show you how I do it…”

It took Karl less than a minute to produce a perfect nail. “Three heats,” he announced. “I’m still slow. We’ll be learning together.”

“I’m tired,” mumbled Gunnar. “And my hands are bleeding.”

“You should have your own anvil, set lower than this. You’re not tall enough, this is a wrong angle for you.” If Karl wanted to cheer the boy up, he failed. Not tall enough, thought Gunnar, who already had a feeling that he wasn’t growing at all, even though he constantly needed larger clothes. “Tell your mother you’ve done well. She’ll bandage your hand. Next week…”

“Weeeeeeek?”

“Once the burns have healed enough. With your hand like this you are not going to do a good job. Also,” said Karl, laughing, “you’ll discover that there are muscles inside your palm. You’ll discover that, because they will hurt. You still need to learn how to hold a hammer correctly. It’s very easy, forging. You spend a few weeks learning the techniques, then a few years getting good at them. I’m not that good either yet.”

“Will I make a sword?” burst out the boy.

“One day,” said Karl, then openly laughed. “You’ll be bored out of your skull. But you’ll have your sword.”

There’s nothing funny about it, thought Gunnar darkly, as Sóley put vaseline on his hand, then tied a dirty bandage around it. The blisters that were open wounds by now were bleeding a bit, the blood mixing with the coal dust on his hands. “Just like your father,” sighed Sóley. “He thinks I’m a bandage factory. Always dirty. Always sweaty.”

Just like my father, thought Gunnar and a little seed of pride began to sprout inside him. Just like my father.

Read about Gunnar’s future in Storytellers, my first novel, available for preorder now, release date March 28.

I never would have thought that making nails would be so complicated!

It really is a great first exercise. In the ol’ times, young apprentices would pay for their schooling by making hundreds of nails – they were always in huge demand before machine production started. (And yes… by sweeping the forge floor over and over again…)